This article was originally published in Sonoma Magazine in 2015.

Like so many birthplaces, Bodega Head was the scene of enormous excitement and hope. It also saw jangled nerves, uncertainty and some very sharp pain. Ultimately, the place was a source of great joy and a deep optimism.

Bodega Head was not the delivery room for a squalling infant, but a bare coastal ridge typically inhabited by more shorebirds than people. Fifty years ago, this granite rise on the outskirts of the small fishing village of Bodega Bay gave birth to an environmental movement that eventually protected the rugged beauty of the California coast. It would inform later anti-nuclear protests and inspire citizen activism for generations to come.

To this unlikely spot and this unlikely town came a colorful combination of grassroots environmental organizers — students, ranchers, dairymen, former communists, far-right libertarians, musicians, young parents, a local waitress and veterinarian, a marine biologist, and even an ornery woman who occasionally carried a shotgun — to join forces. They united in opposition when Pacific Gas and Electric’s (PG&E) decided to build a nuclear power plant on Bodega Head, atop the San Andreas Fault. In a contentious three-year battle that brought the plight of tiny Bodega Bay to the attention of the Kennedy administration, they fought in the halls of justice and actively debated in the court of public opinion. Ultimately, they prevailed, proving that common people with uncommon vision and hard work can indeed change society.

Power to the people

The nuclear age entered the public consciousness with full fury on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945. On that day, in the Japanese city of Hiroshima, the world learned what concentrated nuclear power could do. In a single sharp flash, a nuclear bomb dropped from an American B-29 bomber leveled the city, flattening buildings and vaporizing citizens. Three days later, another bomb fell on Nagasaki. Within a week, Japan surrendered. It was a savage end to a brutal war, and it was also the start of a terrifying new chapter in advanced weaponry. In the next few years, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union would engage in a frantic arms race, building increasingly more powerful atomic weapons, some with the power of millions of tons of TNT.

By 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower wanted to counter “the fearful atomic dilemma” and the scorched-earth reputation of

nuclear energy. In an address to the United Nations, Eisenhower proposed an Atoms-for-Peace Program, designed to quell rising fears of World War III and show how uranium in nuclear reactors could serve as a powerful national energy source. A year later, construction began on the nation’s first nuclear power plant, located in western Pennsylvania near the Ohio border. Eisenhower remotely initiated the first scoop of dirt at the groundbreaking ceremony, and the nuclear age was on.

The West Coast soon followed with its own nuclear facilities. A small experimental reactor went live in Ventura County in April 1957 and a few months later, the Vallecitos Nuclear Power Plant near Pleasanton came online. The Vallecitos project, a joint effort between General Electric and PG&E, was the first privately owned and operated nuclear power plant to deliver significant quantities of electricity for public use. A newsreel at the time boasted that the nuclear-based plant was “one of many that will dot the nation in the near future.”

Those expansion plans soon reached the Sonoma coast. At the start of the 1950s, the 947 acres of Bodega Head were divided among three property owners. The Head was then, as it is now, a stunning piece of land. Some was used for cattle grazing, but most remained as nature intended: sweeping hills of sand, dune grass, jagged cliffs. Miwok Indians first occupied the area, drawn by its abundant sea life and freshwater springs. Later, Russian colonists lived nearby, using the harbor as a base while they hunted the coast for otters, sea lions and seals.

Bodega Head is also alive with birds. It’s part of the Pacific Flyway — a major north-south migratory route that extends from Alaska to Patagonia — and more than 150 bird species have been spotted there. Egrets, herons, hawks and pelicans are common, but a binocular-wielding birder might also see endangered species such as the snowy plover, black oystercatcher and long-billed curlew.

PG&E saw another potential for Bodega Head. The years following the Great Depression were a time of enormous growth in California. Between 1940 and 1946, the population in PG&E’s service area — an enormous stretch of land between, roughly, Bakersfield in the south and Eureka — rose 40 percent. Following World War II, the boom continued. In 1946 alone, 1,200 industries in PG&E’s service area announced plans for new or expanded facilities. PG&E needed to generate more power to serve its customers.

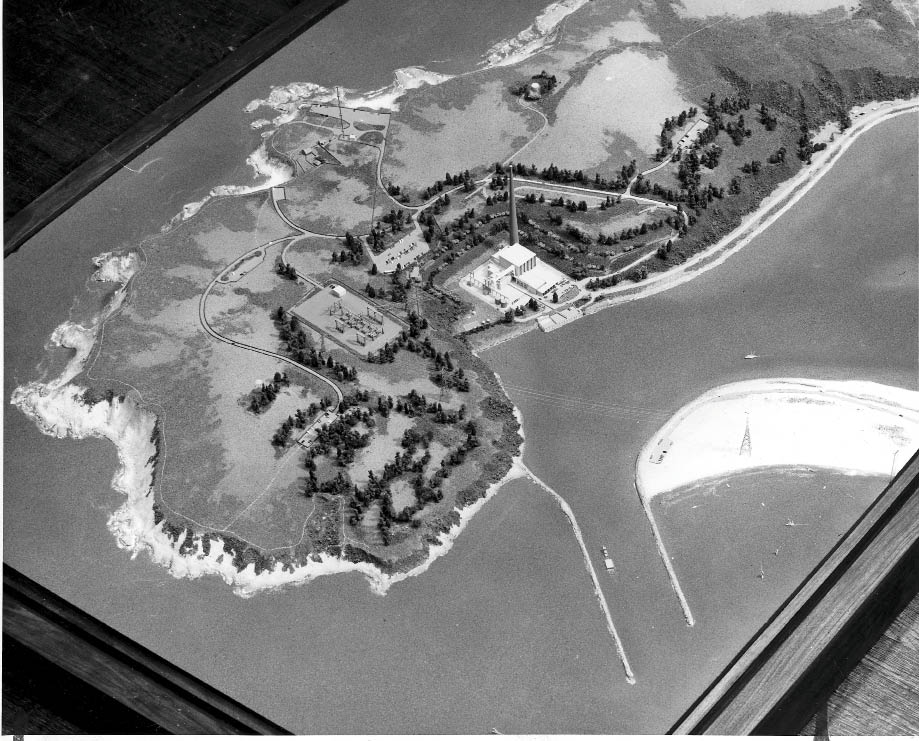

In May 1958, the company acquired property on Bodega Head, revealing plans to build a “steam-electric generating plant” there. Bodega Head was less than 70 miles north of one of the energy giant’s hungriest clients: hundreds of thousands of customers in the burgeoning San Francisco Bay area. The granite ridge of the Head would provide a solid foundation and there was plenty of natural water that could be used as a coolant — Bodega Harbor on one side and the Pacific Ocean on the other.

Locals were flabbergasted. Just three years earlier, the National Park Service recommended that Bodega Head be preserved for its natural beauty. In 1956, the state legislature approved funds to purchase the land and make it a state beach and park. The University of California was interested in building a marine laboratory there. But all those plans swiftly disappeared. The state parks agency said it was no longer interested in the site and the UC system did the same.

PG&E needed more space for its sprawling site, and approached Rose Gaffney about buying her land. Gaffney, a craggy-faced woman who sometimes brandished a shotgun on her ranch to turn away intruders, was interested in selling, but not to the power company. She wanted her 408-acre property to go to the state or the university system. She declined PG&E’s offer. Gaffney later told the Petaluma Argus-Courier that even at that early day, a PG&E official confided to her that the company planned to build a nuclear plant there, “but they didn’t want the public to know yet.”

It pushed on, wooing local politicos. County officials saw the plant as a way to increase tax revenue. Fishermen, however, began to grumble, concerned about soaring water temperatures and construction runoff that might silt up the narrow harbor entrance near Campbell Cove, where the plant was to be sited. There were also aesthetic concerns about the steel towers that would be built through what is now Doran Regional Park to carry the power lines, as well as fears that a planned road to the industrial development would harm wildlife on the shoreline.

But there was more than that. Bodega Bay is a natural harbor created by movement along the San Andreas Fault. The fault extends more than 800 miles through western California, forming the tectonic boundary between the Pacific plate and the North American plate. It runs parallel to the coast and crosses Bodega Bay. The narrow ridge of Bodega Head sits on the Pacific plate, while the town itself is on the North American plate. When the fault shifts, it can do so violently. During the 1906 earthquake, nearby land moved as much as 15 feet; tremors are frequent. As early as 1958, Joel Hedgpeth, the head of the University of Pacific Marine Station at Dillon Beach, began raising questions about earthquake safety and the health of marine wildlife.

Going nuclear

In 1961, finally, PG&E revealed that the proposed plant would be a 340-megawatt nuclear power plant. The state Public Utilities Commission OK’d the permit, subject to approval from the federal Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). PG&E was so confident of future permitting that it began to ready the site, including digging what was designed to be a 90-foot by 120-foot hole to house the reactor. Critics would soon give the giant pit a wry nickname: The Hole in the Head. The Atomic Park, as it was to be called, would be a showpiece. “This was back in the day when nuclear was a wild dream,” said David Pesonen, who would come to lead the movement to foil PG&E’s plans. “They were telling us that one day we could put a pill-sized piece of uranium in your car tank and drive to the moon and back.”

Locals were despondent about the pace of the development and PG&E’s seemingly unfettered race to completion. The town of Bodega Bay, famous as a filming location for Alfred Hitchcock’s horror movie “The Birds,” became the site of something much more consequential. San Francisco Chronicle columnist Harold Gilliam wrote an article lamenting the loss of the coastal beauty of Bodega Bay. Karl Kortum, founder and director of the San Francisco Maritime Museum, wrote a letter to the Chronicle encouraging citizens to write PG&E and oppose the plan. Hundreds did, but PG&E didn’t waver. A nuclear power plant on Bodega Head seemed certain.

But Gilliam’s piece attracted the attention of Pesonen, a junior staff member with the Sierra Club whose life was about to take a dramatic turn. Sent by Sierra Club president David Brower to investigate PG&E’s plans, Pesonen came back a changed man.

“I had a feeling of the enormousness of what we were fighting; it was anti-life,” he said. He recalled a drive he took to the site one day, through a beautiful countryside filled with chicken farms and eucalyptus windbreaks. An accident at the site could make all this land uninhabitable.

“I had an epiphany,” he said. “I began to think that there really was evil in the world. PG&E had a single-mindedness that didn’t involve people’s well-being.”

Suddenly, the fight was a moral issue.

Pesonen left the Sierra Club and in 1962 helped form the Northern California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor. He was articulate and had a sense of strategy. He quickly became the leader.

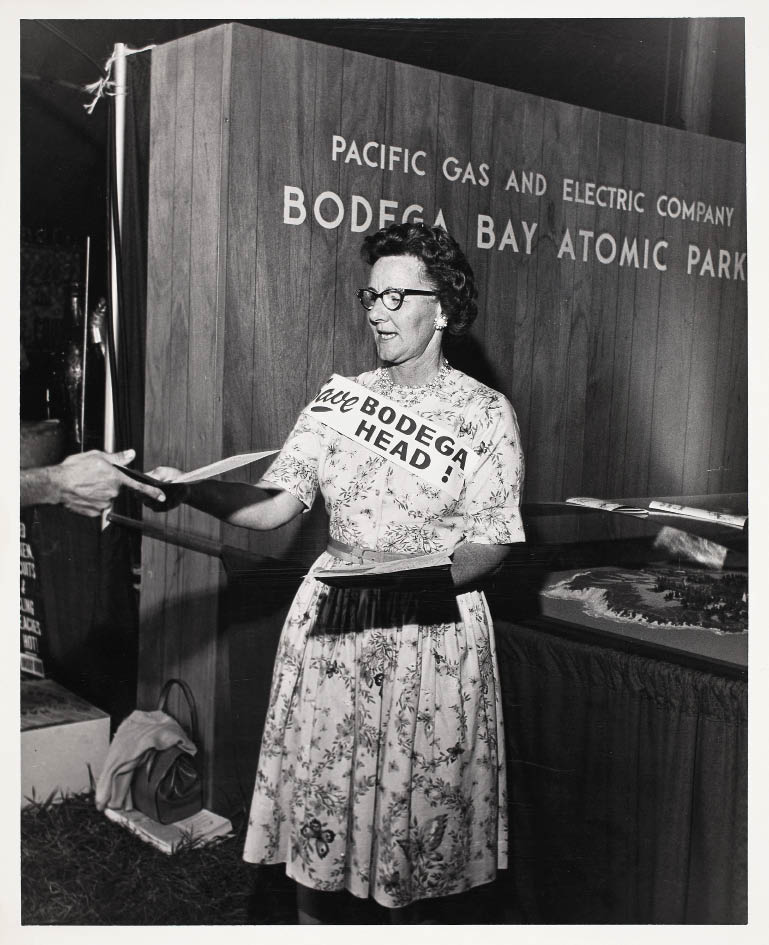

Pesonen reasoned that the group’s members must find an alternative to battling PG&E through the regulatory process, where they was losing. First, they would fight the project in the court of public opinion. During the 1950s and early 1960s, persistent political protests were rare, but the group tirelessly organized rallies, marched with sandwich boards and wrote letters to state officials. Hazel Bonnecke (later Mitchell) spearheaded a petition-signing campaign. Jean Kortum, Karl’s wife, organized sign-carrying demonstrations at PG&E headquarters in San Francisco.

Bonnecke, a waitress at the Tides Wharf Restaurant in Bodega Bay who often served PG&E officials lunch, was said to have tipped off The Press Democrat to PG&E’s nuclear intentions in 1958, although she never acknowledged that role. Hedgpeth’s secretary also was mentioned as the possible whistleblower.

“If not for a few key people, none of this may have happened,” said Doris Sloan, a young mother then, who was a key member in the campaign.

Publicity stunts were fair game. On Memorial Day 1963, organizers released 1,500 helium-filled balloons from Bodega Head. The balloons represented radioactive isotopes, and their random flight dramatized to local dairy farmers how far airborne contamination from the PG&E site could drift, then enter their grass and make its way into the milk. Each had a note attached: “This balloon could represent a radioactive molecule of Strontium 90 or Iodine 131. Tell your local newspaper where you found this balloon.” The balloons descended in San Rafael and Fairfield, and also drifted into the East Bay. Some were found in the Central Valley, more than 100 miles away.

Music became a key part of the protest, Sloan recalled, and the campaign was enlivened with many songs ranging from Dixieland jazz to blues to jug-band music. Celebrated trumpeter Lu Watters came out of retirement to record the “Blues Over Bodega” album, while the Goodtime Washboard Three’s song, “Don’t Blame PG&E, Pal,” even concluded with a menacing explosion.

The group’s trump card, Pesonen believed, was in raising ominous concerns about the reactor’s location on an active fault line.

“PG&E said that if there was any threat to public safety, they would not build it,” Pesonen said. “What tripped up PG&E was the geology of the place.”

PG&E claimed that innovative engineering techniques would eliminate damage to the reactor building in the event of an earthquake. Pesonen and others were skeptical and brought in Pierre Saint-Amand, a respected geologist who prepared the definitive reports on the catastrophic Chilean earthquake of 1960.

“It was a rainy day, the gates were open and there was no construction going on,” Sloan recalled. “The guard wasn’t in the kiosk, so we walked in. Pierre found the fault that runs right through the reactor pit.”

He spent another two days exploring the land nearby. His 46-page report, issued in summer 1963, was devastating. Saint-Amand noted that the site was not the island of granite PG&E had claimed it to be, but a more geologically fractured site. “A worse foundation condition would be difficult to envision,” he wrote. The report drew the attention of Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, who assigned his own investigators to look further into the proposal.

PG&E still maintained that the site was safe and the AEC continued to mull the application, but by October 1963, construction on the reactor pit was halted. In March 1964, southern Alaska was hit with an 8.6 earthquake, the largest recorded in North America. The four-minute temblor buckled streets, liquefied soil, reshaped the shoreline and caused tsunamis. Opponents of the Bodega Head plant pointed to the headlines: Could the same thing happen here? If so, how would a nuclear plant located directly on the fault line fare?

Finally, in October 1964, the AEC released its report on the proposed plant. While noting that PG&E had tried to engineer suitable protection in reactor containment structure in the event of a quake, those “pioneering” designs were unproved and untested. It concluded that “Bodega Head is not a suitable location for the proposed nuclear power plant.” On Oct. 30, 1964, PG&E president Robert Gerdes withdrew its application and canceled plans for the plant.

Miraculously, and against all odds, the protesters had won.

Many of the key figures who represented PG&E in Bodega Bay have died. But at the time, they repeatedly and unequivocally dismissed the protesters’ concerns. PG&E spokesman Hal Stroube, in a May 1963 interview with San Francisco television station KPIX, said the activists’ fears about radiation release were “completely incorrect.” He compared the amount of radiation emanating from the plant on a typical day to be the equivalent of what a family would receive while watching television in their living room. As to concerns about the location’s seismic vulnerability on the San Andreas Fault: “We would simply overdesign the plant,” Stroube countered. “We have built 76 plants (in California) … and every one of those is built with earthquake possibilities uppermost in mind. We have to keep these plants running in the event of an earthquake or any other civil commotion.”

A half-century later, PG&E remains philosophical about its defeat. “PG&E’s decision to withdraw from the project is demonstrative of our No. 1 priority, and that is to always put safety first,” said Blair Jones, a PG&E spokesman based in San Luis Obispo. “Our decision to not pursue it does not in any way reduce the overall benefits that nuclear-generated power continues to provide to our customers and other utility customers around the nation. Nuclear power is a significant supplier of clean energy to Americans.”

A turning point for many lives

When the site was abandoned, the reactor pit had been dug more than 70 feet deep. It has since filled with water, replenished by the natural springs that drew Miwoks to this location thousands of years ago. Today, the Bodega Head power plant site is a serene pond, lined with reeds and filled with noisy birds. There’s little to remind a casual visitor of what almost arose here.

On Oct. 30, 2014, the 50th anniversary of PG&E withdrawing its plans, the remaining veterans of the Bodega Head fight gathered for a luncheon at the Hyatt Vineyard Creek Hotel in Santa Rosa to again celebrate their victory. While their frames are stooped and their hair is gray, their spirit remains young. They’re still witty and warm and are keen to talk about political issues. And they still dislike PG&E.

The room was filled with laughter and love. Many said the fight to save Bodega Head changed the direction of their lives. Sloan, for instance, went on to help establish an environmental studies program at UC Berkeley, and was involved in many local environmental movements, including Save The Bay, which works to protect and restore San Francisco Bay. Bill Kortum, brother of Karl, was just starting his veterinary practice when he joined the campaign. It led to a lifetime of environmental activism, including helping to establish the California Coastal Commission. Jean Kortum, Karl’s wife, played a key part of the 1960s Freeway Revolt that halted the construction of major highways through San Francisco. The projects were wildly supported by the city’s politicians and labor leaders, but were defeated by citizen opponents.

“This kind of fight got into our DNA,” said Julie Shearer, then a young reporter for the Mill Valley Record who was married to Pesonen during the Bodega Head fight. “It made us all more alert, more responsive and more active for the rest of our lives.”

Pesonen agreed. “It was the turning point in my life,” he said. Pesonen later attended law school at UC Berkeley and was active in the anti-nuke movement, leading the Sierra Club’s opposition to PG&E’s ill-fated nuclear power project at Point Arena. He later became director of the California Department of Forestry in the late 1970s and was also a superior court judge.

These environmental elders, as they’re called, made an important statement: Economic growth and technology must not trump respect for the land. Their unlikely victory was a revelation and an inspiration to many. In the late 1960s, similar citizen opposition grew in Southern California near Malibu, where the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power had proposed to build a nuclear power plant in rugged Corral Canyon. Following a string of activist protests and actions, the Malibu plant project was dropped in 1970.

“People saw that they could speak up, take on major institutions and win,” Bill Kortum said in October. Ultimately, the action of a few tireless crusaders launched an environmental preservation campaign that continues today. The movement “grew because we were persistent,” Pesonen said.

But just as importantly, he noted: “It grew because we were right.”

![3/10/2002: D1: The site of PG&E's nuclear power plant, under construction in 1963 at Bodega Head. (John LeBaron/ The Press Democrat) [Hole in the Head]](https://d1sve9khgp0cw0.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/BODEGA_50130-1200x1042.jpg)

![04/17/2011: G11: PC: 1964_Bodega head / PG+E Plant 4/18/2004: A8: In 1959, debate over the decision to build a PG&E nuclear power plant at Bodega Bay intensified, ultimately leading to the plan being abandoned in 1964, after construction was under way. [Hole in the Head]](https://d1sve9khgp0cw0.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/PGE_PLANT_153866-1200x872.jpg)