John Carl Warnecke designed the South Terminal at Logan International Airport in Boston, the Hart Senate Office Building in Washington D.C., the master plan for UC Santa Cruz, and major projects in Asia, Europe, the South Pacific and the Middle East.

But the peripatetic visionary who most famously designed the gravesite for President John F. Kennedy in Arlington National Cemetery, and who at one time headed the largest and most diverse architectural firm in the world, considered home base a 245-acre ranch along the Russian River on Chalk Hill that had been in his family for a century.

Here, starting in 1960, “Jack” Warnecke carved out a singular family compound for his four children that paid careful respect to the land. And while his work took him all over the world, Warnecke would always come home to his “special place on the river” to power down, as well as to welcome his many associates, clients and friends, a wide, eclectic and influential circle that including Sen. Ted Kennedy, the Grateful Dead and the first delegations of Russian and Chinese architects to come to the United States.

He also envisioned this spot, with its striking vistas of mountain ranges and one of the best steelhead and smallmouth bass fishing holes on the Russian River, as a rural getaway and salon for the best and brightest minds in the world of architecture, preservation, urban planning and the arts.

It was a place both casual and refined, where Warnecke and his second wife, Grace Kennan McClatchy, the daughter of diplomat George Kennan, would canoe and ride horses, serve barbecue or sip Russian vodka while engaging in erudite conversations by candlelight.

The heart of the ranch is the 60 acres of riverfront land he inherited from his maternal grandfather, George Esterling, who purchased it in 1911. Over the years, Warnecke acquired neighboring ranches to create a vast retreat, situated on a 1-mile U-turn of the river that creates a private, hidden valley. It is also within or surrounded by the Alexander Valley, Chalk Hill, Knights Valley and Russian River Valley viticultural areas.

Three years after his death in 2010 at age 91, Warnecke’s heirs are of a single mind to preserve the ranch as he left it, including 70 acres of vineyards, and to move forward his dream of making the ranch available as a recharging station for artists. They’ve already created the Chalk Hill Artist Residency, setting aside an old farmhouse with nearby studio space for select artists and composers to spend two weeks to two months on a special project, drawing inspiration from the land.

“He knew we all loved it and it was going to be in good hands,” said Fred Warnecke who, at 60, is the youngest of the architect’s four children. “He had set up all these plans and long-term goals of things he’d love to see happen. That was a great outline for us to proceed.”

A landscape architect, Fred now lives full time on the ranch. He once spent idyllic summers roughing it in platform tents set up beside the Brick House, a family lodge for dining and recreation with 14-foot ceilings, wide oak-plank floors and a big porch overlooking the river.

His daughter, Alice Warnecke Sutro, 29, an artist, lives in a cottage on the ranch with her architect husband, Eliot, and helps to manage her grandfather’s land and legacy alongside her aunt, Margo Warnecke Merck.

“We all grew up here in the summer and that’s how we all just fell in love and got our passion for the ranch. It was like an amazing summer camp,” said Merck, who for years helped manage her father’s firm out of New York after receiving a master’s degree in architecture from Columbia University.

It was her brother, Rodger, who brought her back to Sonoma County in 1996, and whose struggles with mental illness inspired a key component of the Chalk Hill Artist Residency program.

A gifted artist, Rodger was recognized as “the next Frank Stella” while attending the prestigious Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass. Stella was a celebrated minimalist and post-painterly abstract artist and Andover alumnus. But Rodger’s promising career imploded during his first year at Stanford University, when he was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

“His work,” Merck said softly, “got smaller and smaller” until he stopped drawing altogether. Rodger spent years in a locked mental facility in Eureka, and Merck became her brother’s fierce supporter when he was released to a board-and-care facility in Sacramento.

“I said, ‘absolutely not. We want Rodger around as family,’” declared Merck, who bought a nearby ranch with her husband, Al Merck, and became a forceful advocate for permanent housing for the disabled and mentally ill in Sonoma County.

Rodger’s artistic drive returned with the arrival to market of the schizophrenia drug Clozaril in 1994, and now he enjoys coming to the ranch to work on his abstract paintings and intricate notebook drawings.

“The first thing he said after 25 years was, ‘I see light. It’s like I’m at the bottom of a river looking up, and I want to paint again,’” Merck recalled.

Artists who are selected for the residency program are asked to spend a day interacting, supporting and sharing ideas with outsider artists from area nonprofits that serve the mentally ill.

Mental illness is a cause of great importance to the Warneckes. Jack’s oldest son, John Jr., an early road manager for the Grateful Dead who died of a heart attack 10 years ago, suffered from bipolar disorder.

Rosemary Milbrath, executive director of the Sonoma County chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, calls the Warnecke Ranch “a healing place.”

“Our clients get to go up there and work with established professional artists,” she said. “Many of them are living in little one-bedroom apartments or group homes and they don’t even get the chance to be in a beautiful, natural place like that.”

Alice Sutro, who oversees the program, said it helps artists with disabilities “feel special and considered as professional artists.”

With converted barns, cabins, houses, carefully designed park-like grounds, gardens and wild open spaces, the ranch is as big and multifaceted as Jack Warnecke himself.

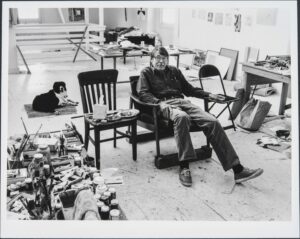

He was a formidable presence in both figure and personality. A Stanford football left tackle on the school’s undefeated “Wow Boys” team that won the 1941 Rose Bowl, Warnecke vaulted into rarified circles. Through a mutual friend, he was introduced to John F. Kennedy, who recruited him to come up with a historically sensitive redesign of Lafayette Square across from the White House.

After the president was assassinated, his widow, Jackie, turned to Warnecke to design JFK’s monumental gravesite, marked by an eternal flame. During the process, the pair became lovers.

“They loved each other equally and strongly and passionately,” said Fred Warnecke, who spent a summer in Hawaii with Jackie and even babysat her children while his father worked on the state capitol building in Honolulu.

Fred said he was told that the relationship fell apart when Robert Kennedy counseled Jackie that Warnecke, who was always on the move and whose business fortunes rose and fell, couldn’t provide the stability she needed. But the architect maintained a lifelong friendship with the former first lady and other members of the family. A wall in an art-filled home he created for himself on the ranch is filled with photos of the charismatic Kennedy clan.

Warnecke left a remarkable architectural legacy. A converted milk barn on the ranch contains his vast archives — photographs, maps, blueprints for everything from university buildings to embassies to a luxury motor home for a Saudi prince, and master plans for projects such as D.C.’s Pennsylvania Avenue. It also houses the archives from the work of Warnecke’s father, noted Bay Area architect Carl Warnecke.

Family members love giving tours to architects, planners and other design researchers. But they also simply love sharing the ranch, just as Jack Warnecke did, inviting in school groups and periodically holding open houses so the public can explore the land he loved.

“After he passed,” said Merck, “there was so much work. But we’re getting there and we’re feeling excited.”