Editor’s Note: Shaun Michael Gallon, a Forestville man and ex-felon, admitted in a Sonoma County courtroom Thursday to the 2004 murders of Lindsay Cutshall, 22, and Jason Allen, 26, bringing an end to the county’s most unsettling cold case in a generation. Here is an in-depth look at how this tragedy affected the family, locals and investigators, published in Sonoma Magazine in 2014 on the 10-year anniversary of the murders.

The Pacific Ocean, silver-flecked by the sun, pulls at the slight curve of Fish Head Beach. It’s been a decade since a devout young couple from the Midwest were murdered on the gray sand just north of Jenner. Most days, a salted wind bites at the steep bluffs they would have had to descend to reach the shore.

Except for the startling beauty, there is no visible memorial to Jason Allen and Lindsay Cutshall, shot dead there in 2004 as they slept on the beach, their Bible nearby.

The crime stunned the region and captured national attention. It remains unsolved, the killer or killers still unknown.

“The ugly outside world visited us that night,” said Thomas Yeates, a 30-year resident of Jenner. He spoke this spring in the village of some 140 people, with seaside inns and vacation cottages, a state parks visitor center, a post office, and a gas station-deli.

Yeates, 59, had strolled Fish Head Beach recently with his girlfriend, who is new to the area and unaware of what happened there. While he cannot forget the crime, he did not want murder to cloud their day.

“I didn’t want to bring it up,” he said. “And I didn’t.”

Praying for the ‘enemy’

Lindsay Cutshall grew up in Fresno, Ohio, some 2,500 miles east of Jenner. It has a small post office and a few dozen homes scattered at a distance around some railroad tracks on the edge of Ohio’s Amish Country, where narrow roads carry horse-drawn carriages and wind past red barns and fields of hay and corn.

A “broken” man who would have it no other way lives there: Pastor Chris Cutshall, Lindsay’s father. God can use him fully now, the pastor says.

On the first Sunday in May, Cutshall, 59 and still wiry like the wrestler he was in high school, stood before 217 Fresno Bible Church worshippers — almost the entire congregation — from babes in arms to slow-moving seniors.

He no longer carries his slain daughter’s well-marked Bible when he preaches, as he did for several years; not every sermon can spring from the passages she highlighted. But Lindsay’s name and death — and Jason’s, too — now inhabit the vernacular of the evangelical Fresno Bible Church.

His sermon that day was titled, “The priority of love.” Near its conclusion, Cutshall said to his rapt parishioners: “Did you know that Kathy and I, we pray for the man who killed our kids?… He’s our enemy, but he’s a person in need.”

Faith in God is virtually inseparable from the lives and deaths of Lindsay Cutshall and Jason Allen, 22 and 26, respectively, when they were killed.

It is inseparable from how memories of them are held by their parents, whose deep religiosity promises them a reunion with their children and embraces even their killer. In some cases, it is inseparable from those who track the killers: law enforcement officers who hew to a strong Christianity or, in the murders’ wake, adopted a fervent new faith.

For all that, for how they have forged on, for the way the Fresno Bible Church that Lindsay grew up in has thrived since her death, for how, subsequently, disparate people found the same Christ they worship, the Cutshalls and Allens are grateful and awed.

“Yes, it was a horrible tragedy, an evil thing, but God can still take that and use that for good and for his glory,” said Delores Allen, 62, Jason’s mother, seated with her husband, Bob, in the sunroom of their home in Zeeland, Mich.

Outside the house, the lawns are wide and, for the most part, no fences separate them. The town is a flat landscape; the welcome sign at its border celebrates the championships brought home by the high school sports teams.

Jason grew up there, ensconced in the Baptist faith that has sustained his parents.

“We have the assurance that we know where they are and we know we will see them again,” Delores added. “I know that not all parents have that, and that would be unbearable. If I didn’t have that assurance that they are alive, I don’t know if I could deal with that.”

Driftwood that Jason collected, and also some retrieved from the beach where he was killed, accents the room. It comforts him, said Bob, 67. It reminds him both of Jason and of God’s will, of which he was informed soon after his son’s death.

Days after Jason was killed, Bob learned that not long before, Jason had fallen while rappelling from a 30-foot cliff and narrowly missed a formation of boulders. He went to the spot after his son’s death. Standing there, he said, he heard God’s voice:

“The Lord spoke to me really plainly and he said: ‘Yes, I saved Jason from dying on these rocks. And yes, I could have saved him from dying on that beach. But this is for my glory.’ ”

‘An uphill battle’

It was one of the North Coast’s most notorious slayings, garnering coast-to-coast media coverage, and it remains so 10 years later: the murder of a fresh-faced, young couple in love.

Lindsay and Jason, who met at a Bible college and planned to spend their lives ministering to Christian youth, were to marry Sept. 11, 2004. But they failed to show up Monday, Aug. 16, at their summer jobs as counselors at Rock-N-Water, a Christian youth adventure camp in California’s El Dorado County.

The couple had departed Friday night for a weekend trip; it is believed they planned it at the last minute after a full day of whitewater rafting with their youthful charges.

“I had just sent out the wedding invitations and I came back that (Monday) morning and got the call from camp: ‘Jason and Lindsay are missing,’ ” said Lindsay’s mother, Kathy Cutshall, 57, speaking after a hearty lunch of pulled pork in May in the Cutshalls’ cozy mobile home on the church grounds. “My heart dropped. I knew something was wrong.”

The Cutshalls flew out on Tuesday, the Allens on Wednesday. Both couples landed in Reno and drove to Placerville, where they would stay at the home of Craig Lomax, the camp’s owner and director.

Kathy called a friend of Lindsay’s who worked in the Ohio bank that had issued Lindsay’s credit card, and asked if he could help. Was it ethical? she asked.

“He said, ‘It doesn’t matter,’ ” she recalled.

The couple were traced through credit card receipts to San Francisco, where Lindsay had bought a miniature bottle of Tabasco sauce at Fisherman’s Wharf on Saturday. Late Wednesday, their bodies were found on Fish Head Beach, a mile north of Jenner. It was later concluded that they were killed between Saturday night and Sunday morning.

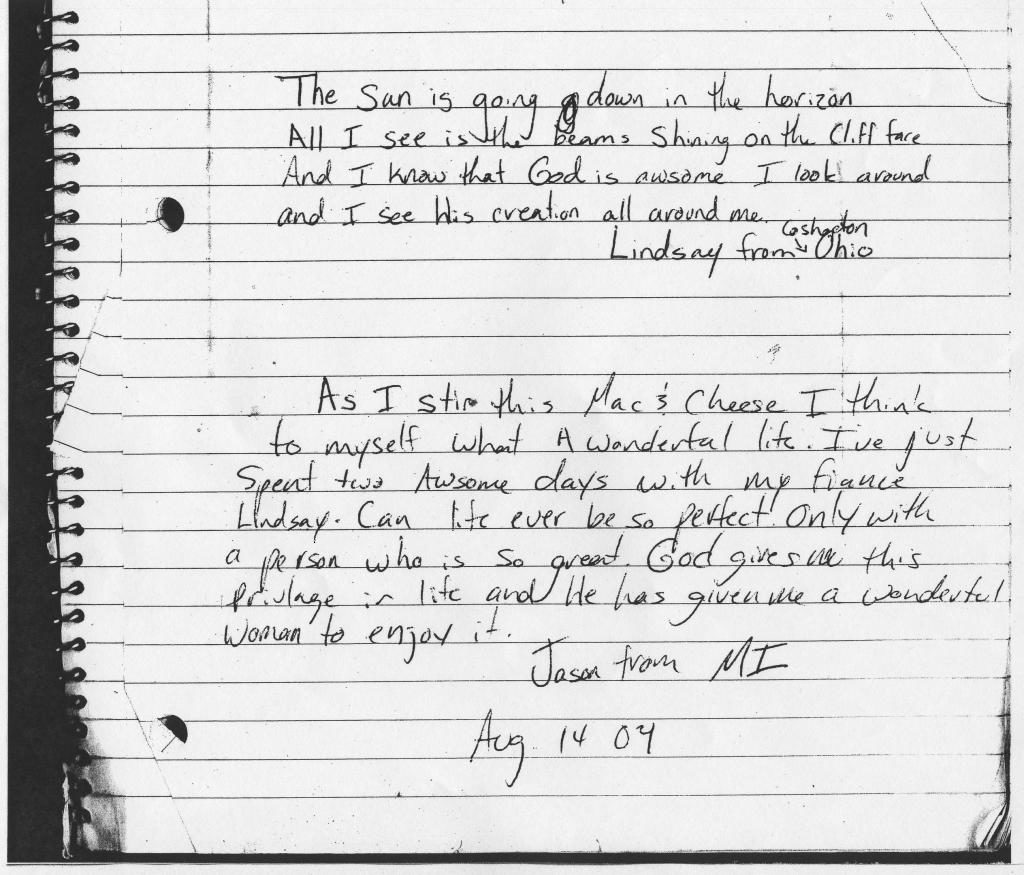

At some point, they had made entries in a sort of visitors’ journal that was kept in a small wooden hutch on the beach.

“The sun is going down in the horizon,” Lindsay wrote. “All I see is the beams shining on the cliff face. And I know that God is awsome (sic). I look around and I see his creation all around me.”

Jason wrote: “As I stir this Mac & Cheese I think to myself what a wonderful life. I’ve just spent two awsome (sic) days with my fiance Lindsay. Can life ever be so perfect. Only with a person who is so great. God gives me this privilege in life and He has given me a wonderful woman to enjoy it.”

They were found in sleeping clothes and separate sleeping bags. Each had been shot once in the head at close range with an uncommon rifle: a Marlin .45-caliber that uses ammunition also suited to handguns.

The crime was confounding, as was the scene.

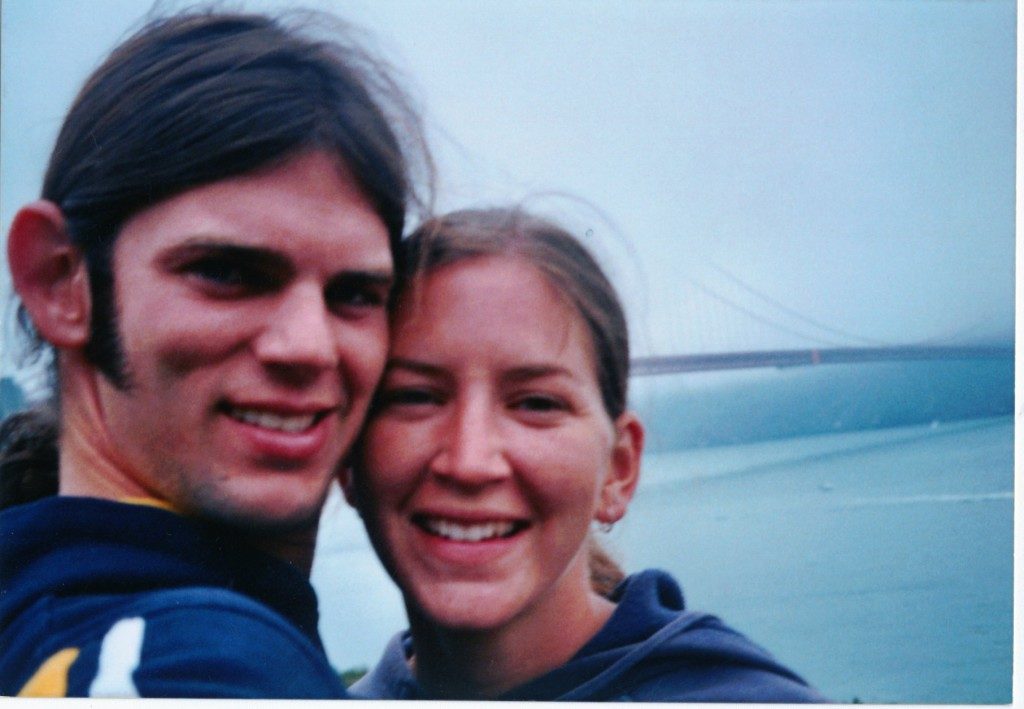

Nothing, including their camping gear, appeared to have been stolen. Their car, a battered red Ford Tempo parked in a pullout spot on the side of Highway 1 in Jenner, was untouched. The couple had been in Sonoma County for a matter of hours — a photograph in a camera found with them showed they had been at the Golden Gate Bridge earlier Saturday — and knew nobody here. There was no sign of sexual assault. Lindsay was still wearing jewelry including a diamond cross necklace. The couple’s positions in death led investigators to conclude they had been asleep when shot. And the crime scene, in a remote location, had been exposed to the elements for four days.

“We were behind the eight-ball from the start. We had an uphill battle to fight,” Dave Thompson, a Sonoma County Sheriff’s detective who worked the investigation for two years, from its start, said in an interview in May.

Investigators plunged in, positive nonetheless. The five-person Violent Crimes Investigation (VCI) unit was among 25 detectives on the case.

“We had just come off a couple of other cases that were solved, the unit was clicking, and we were going to attack this one and hopefully come to the same conclusion,” said Thompson, now 44. “That was our mind frame: ‘We’ve been handed this thing. Let’s get going.’ Everyone was on their game.”

The vow

On Thursday, Aug. 19, at 6:30 a.m., a group of men approached Lomax’s house at the camp with terrible news.

Now, the recollections of precisely who was there vary. In Thompson’s memory, it was him, Lomax, an El Dorado Sheriff’s Department chaplain and Sonoma County Sheriff’s Sgt. Steve Freitas, then head of VCI. Freitas, now Sonoma County Sheriff, wanted Thompson there because of the detective’s deep Christian faith.

“I brought him basically to interpret the Christians for me,” said Freitas. He had no idea of how the murder case, merely one of 60 or more he has worked on, would change his life.

Chris Cutshall and Bob Allen, sensing what was to come, met them outside.

“It was like, ‘We’re the men of the family. We’re here to take the bad news first,’ ” Thompson said. “We gave it to them. It just confirmed what they had already suspected.”

Then the fathers told the mothers.

“It was almost unreal. They didn’t know anybody. How could they have gotten shot?” Delores said. “And on a beach. Who would have done that?”

“I said to Chris, ‘I can’t do this,’ ” Kathy recalled. “He said, ‘We might not have a choice.’ ”

Detectives began interviewing camp employees, in rooms at opposite ends of the house. The Cutshalls and Allens sat together at the dining table.

They prayed. They wept. They promised they would withstand the devil.

“The four of us made a vow,” Chris said. “That we weren’t going to let Satan have any victories in our lives. That was the vow, that we weren’t going to fall into sin and lose to the devil. He didn’t deserve it and we weren’t going to let it happen.”

A fruitless search

Hundreds of tips poured into the sheriff’s office in the first few days of the hunt for the killer. Detectives quickly broadened their search to outside Sonoma County, looking at similarities in unsolved murder cases in Humboldt County and Arizona to see if there were links.

A drifter — a Wisconsin native still on the road 10 years later — was named a person of interest. He took a polygraph exam and was cleared of involvement.

Coastal residents were shaken.

“Living out on the coast, away from big cities, it’s not something we’re used to,” said Nick Marlow, then a Duncans Mills resident. He purchased a gun soon after, he said, partly in response to the events.

“It was a shock … and resonated throughout the community,” said Marlow, 38, now of Occidental.

Tipsters in the coastal region reported an unfamiliar car with a distinctive decal on its window in the area at the time of the murders; detectives circulated hundreds of fliers.

The rare Marlin rifle was publicly identified as the murder weapon. Detectives went door to door in the county and elsewhere looking for that model of gun, eventually taking about 100 firearms to test.

The weeks wore on and theories abounded: that the couple had stumbled upon a drug deal or an abalone-poaching ring; that they had angered someone by evangelizing or otherwise speaking too openly about their faith. Chris was convinced that one man had stalked the couple.

More time passed. The state posted a $50,000 reward. It is still unclaimed.

Into the fold

As the investigation proceeded with no apparent progress, developments occurred on other fronts that the Cutshalls and Allens have come to see as being of equal importance: People touched by their childrens’ deaths began committing their lives to Jesus.

A future sheriff was one.

As Freitas met Chris Cutshall and Bob Allen to break the news, he also carried another weight. His marriage, strained by factors including his intense commitments at work, was in serious jeopardy.

That was secondary, though, as the moment came to tell the fathers what had happened to their children.

Freitas, 51, still shakes his head when he remembers Cutshall’s reaction.

“When I told those two men that their kids were dead, Chris Cutshall was overjoyed,” Freitas said. “I can remember this day vividly still. In my head, I thought, ‘This guy’s crazy or he’s on drugs.’ ”

On the return trip to Sonoma County, Freitas, taken aback by Cutshall’s response, quizzed Thompson, the stalwart Christian, about his beliefs.

“It didn’t make sense to me, but Dave was able to help explain it to me,” Freitas said. “(Chris) was so happy that his daughter was in heaven and there was no question in his mind that she was in heaven: ‘She’s in heaven and heaven’s a better place than this and I can’t wait to be there with her. Everything’s good.’ ”

For several years prior to the murders, Freitas, who grew up without religion and with no inclination toward it, had been experiencing occasional events that compelled him, he said, to wonder at the possibility of a God.

For example, he said, a congregation he had visited, as a Sheriff’s Department representative, had prayed for him and his wife, who were trying without luck to conceive. A month later she was pregnant.

Still, he said, “I had totally no faith in my life.”

But Cutshall’s reaction, he said, opened the door.

“It was just so … just so sure. He was on such solid ground with that,” Freitas said. “I don’t even know how to explain it. It was just a powerful, powerful thing. It made me very, very curious.”

At some point in those early, awful days, Cutshall recalled, he and Freitas sat in the kitchen and talked, about the case, about their families and about faith.

“He struggled with the whole idea of how a good God could allow innocent kids like ours to die,” said Cutshall, speaking after the worship service as his grandsons, Jackson, 6, and Lucas, 3, played at his feet.

“It really gave me the opportunity to talk about God’s goodness, right after we found out,” Cutshall said, “to witness to him of God’s goodness. I remember him just shaking his head.”

Those conversations resumed months later, after Freitas left VCI. And then there was a moment in 2005, at a dedication ceremony at Rock-N-Water camp of a plaque for Jason and Lindsay, that Freitas, chatting with Cutshall in the woods, said he accepted Jesus Christ as his Lord and Savior.

The murders, said the sheriff, “changed myself and my family.” It led to a faith, which his wife and sons now share, that he believes saved his marriage.

“There is no doubt in my mind that we would have absolutely gotten divorced, if we did not find faith,” said Freitas, who now worships at an evangelical church in Windsor.

The Cutshalls and Allens refer to events such as the sheriff’s discovery of faith — others have included a television journalist and a Brazilian woman who has adopted Cutshall as her surname — as “Lindsay and Jason fruit.”

“When I tell our story in testimony,” said Chris Cutshall, “I usually use the Freitas family as an example of God’s goodness. God causes all things to work together for good to those who love God.

“Out of this awfulness, this tragedy that was very personally experienced, we’ve seen God keep that promise.”

‘It has not gotten cold’

“It’s always in the back of my mind, just like it has been for the last 10 years,” said Sheriff’s Lt. Carlos Basurto, who oversees VCI now and was one of the first detectives to set foot on Fish Head Beach on that Wednesday in 2004.

Perhaps the brightest hope for a resolution to the case came in 2009. Joseph Henry Burgess, a fugitive wanted in connection with the 1972 slaying of a young Christian couple as they slept on a Vancouver Island beach, got into a gunfight in New Mexico in which he and a sheriff’s deputy were killed.

Sonoma County detectives flew to New Mexico to see if there were ties between the 1972 case and the killings of Jason and Lindsay. But Burgess’ DNA did not match that found on a beer bottle discovered at the scene of the Fish Head Beach murders.

That didn’t exclude Burgess as a suspect, but it meant he could not be connected to the slayings through any other means — by anything in a dozen 4-inch binders of tips, for example, or piles of boxes of investigative research.

“It was extremely frustrating, extremely frustrating,” Basurto said. Still, detectives continue to work the case.

“Although it’s considered a cold case, it has not gotten cold,” he said.

In February, detectives flew to the East Coast — Basurto won’t say where — to interview a “person of interest.” There have been no public developments as a result, but that angle remains open, Basurto said, and other persons of interest are also being explored.

Several viable tips come in monthly that detectives track down, and at times are solid enough to mobilize the unit.

“We’ve had so many different leads that were burning hot … that ended up flaming out,” Basurto said.

The case is, in some ways, a sore point.

“It seems like a black eye, on my tenure, at least, in VCI,” Thompson said.

But the Christian in him, as well as the veteran law enforcement officer, holds out a strong hope.

“One of these days, there’ll be some sort of break,” Thompson said. “I know there are enough people still working on it, still thinking about it and still praying about it.”

When it comes to the possibility that one day they might know who killed their children, “closure” is not a word that the Allens and Cutshalls use. They concede an interest in the killer’s capture — she would like to ask him why, Delores said. Chris said he would like to have him ask their forgiveness. But in conversation, those concerns seem overshadowed by their commitment to forgiveness and their certainty that the killer will one day face a superior judgment.

“We believe in the justice system, too, and we know there are consequences to sin and we would like to see the person caught,” Delores said

“And brought to justice,” added Bob.

“And brought to justice,” echoed Delores. “But it would be a miserable life if we were so absorbed in anger and bitterness that we lost our joy and we don’t want anybody to have that power over us, to take joy from our lives. That’s why we give it to the Lord, knowing he is the final judge.”

Chris Cutshall said he also pities the killer, foretelling for him a stern fate.

“That guy doesn’t have to face the pitiful anger of a little human being, of a father,” he said. “He has to face the wrath of God. And knowing scripture and believing scripture as I do, that’s an awful thing. I wouldn’t wish that even on him.”

Grieving and healing

The mothers could not enter their childrens’ bedrooms for several years after the murders.

For nearly three years, Chris Cutshall would periodically find himself flat on the floor, sobbing.

Bob Allen thinks of hunting with his son, and the loss hits him in his gut.

“Jason was an excellent shot,” he said with pride.

For all the prayers, for all the faith, the pain still arrives — Mother’s Day, birthdays, holidays. On any day.

A week before being interviewed in early May, Kathy Cutshall, out of the blue, was weeping.

“It’s almost like a homesickness,” she said.

There still are days when she goes to her part-time job in a jewelry store and cannot stay.

Delores still finds herself crying at times when she comes across things that belonged to Jason.

“They are not unaffected,” said Janna Kuiphof, 36, a childhood friend of Jason’s in Zeeland who is still close to the Allens, and who has come to know the Cutshalls. “There still is a deep and profound sense of loss and sadness because Jason and Lindsay not being here has left a noticeable hole.”

But the families have survived almost unimaginable loss. Indeed, they appear to have thrived.

They have been helped by the almost certain knowledge that their children were sleeping when they were shot.

And for the Cutshalls, in particular, the fact that no evidence of sexual assault was detected has softened the tragedy.

“There were some things that I think God knew I couldn’t handle. And one was if there had been torture,” Kathy said. “Or if I knew they had pain. And he (God) took care of that.”

“It would have been much worse,” Chris added, his voice far flatter than usual. “It would have been much harder. I mean as bad as it is: our daughter got shot in the head, and our son, basically. Awful. But it could have been worse. And I’ve always been thankful for that.”

The arrival of grandchilden has also played a large role in the recovery of both families, each of which has other children. But indisputably, it is their faith — and the belief that positives have sprung from the tragedy — that have steered them to a place where peace of mind and heart is possible.

“There is a lot of good that has come, and they’re in a wonderful place, and if I didn’t know or feel that, it would be quite different,” Kathy said. She acknowledges, though, that to come to that point took years.

“At the beginning, when I’d hear people say that, I used to want to just shake them,” she said. “But I’d think, ‘No, I wouldn’t want anybody to know that kind of deep pain.’ ”

Delores and Bob say the unexpected ability to live without rage at the killer has been a blessing.

“The more the anger builds, the more it tears you down,” Bob said. “We were able to give that anger to the Lord, so we’re not angry.”

“We don’t hold any anger or bitterness to this person. We know that this person is a lost soul,” Delores added. “And Jason and Lindsay dedicated their lives to bringing good news to those people who are lost.”

Cutshall has flourished as a pastor, the congregation is more solid than it was before the killings, and his power as a Christian minister has grown.

“We are a faith family,” he said. “There’s a lot of love there and that has increased quite a bit since Lindsay died. It has deepened our love and compassion for each other.”

He added, “I think it’s deepened the church’s respect for me. It gave me clout. Before I would get, every once in a while, ‘You don’t understand. You haven’t gone through what I’ve been through.’ I don’t get that anymore.”

He sees God’s hand at play in “selecting” the families who were to go through their ordeal.

“We were both theologically, spiritually on the same page from the very beginning. We were ready. That’s always struck me,” he said. “It’s almost like we were called to this and God knew what he was doing, so that God could be glorified and Satan couldn’t win in our lives.”

Still, Cutshall, who wears a ring of his daughter’s on the little finger of his right hand, doesn’t like to visit the gravesite near Fresno where Jason and Lindsay’s cremated remains are buried together — as if they had married — in the same casket.

Faith, he said, is not, and should not be, an exemption from sorrow.

“The biggest fear I’ve had over the years is that I wouldn’t grieve over her any longer,” Cutshall said. “She’s worth it. She’s worthy. I’m her father. This is her mother. We feel kind of fearful to get to that place where we wouldn’t anymore. We don’t break into tears all the time anymore. But we still grieve.”