His birth name is Sam, though he won’t divulge his last name and wants the world to call him Fat Dog, a nickname given to him by his mother.

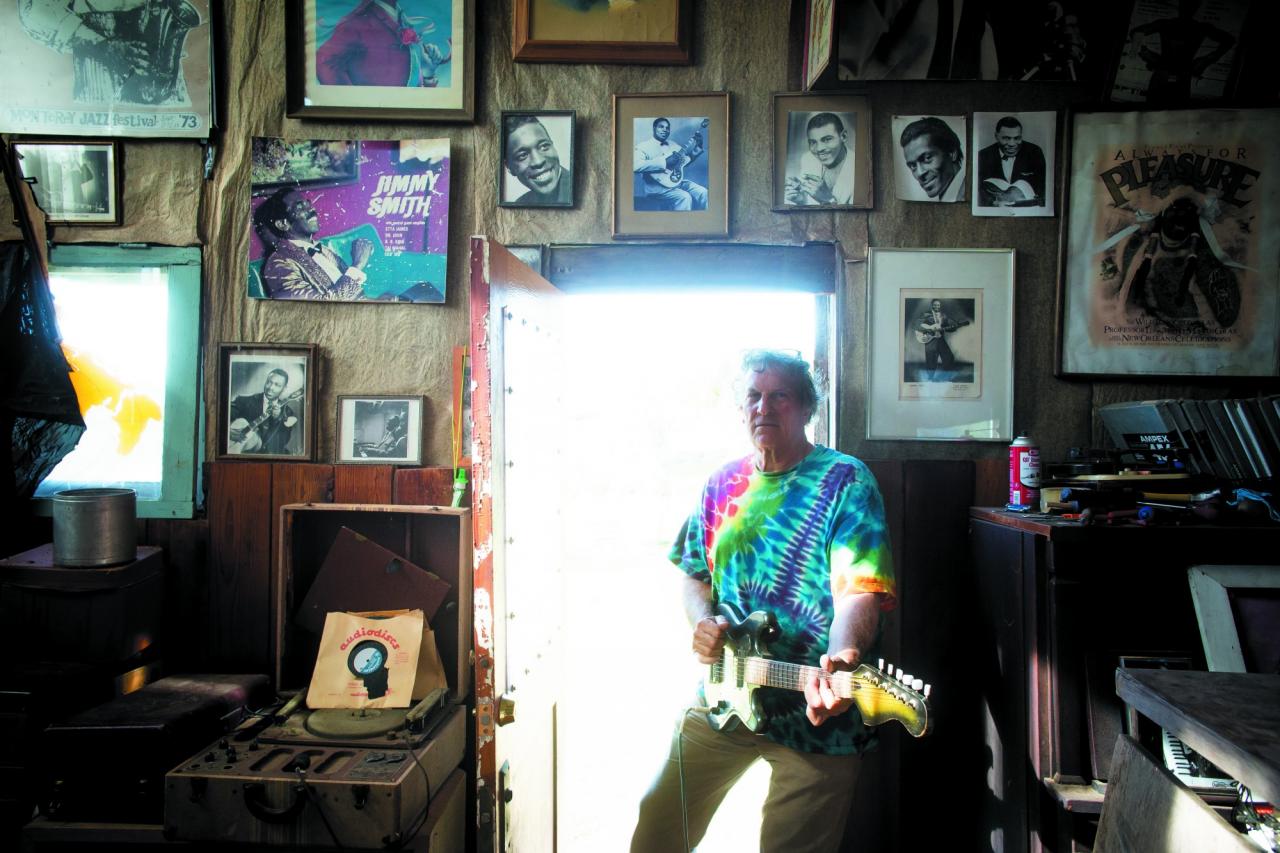

He doesn’t want the exact location of his home and recording studio revealed, though it’s somewhere above Sonoma Valley. Fat Dog, 68, has never married, doesn’t have kids, doesn’t own a cellphone and is fond of wearing tie-dyed T-shirts and jeans. He makes his living running Subway Guitars in Berkeley.

So hippie. So Sixties.

Yet Fat Dog lives very much in the now, his somewherein-Sonoma music studio and guitar workshop welcoming musicians to play, record and rebuild instruments with him. Some are students from Bennington College in Vermont, who earn credit while learning how to assemble guitars. Others are accomplished musicians who appreciate Fat Dog’s efforts to make guitars affordable to all, and his ability to construct instruments specific to their needs.

One of the instruments he made recently was for Joseph “Ziggy” Modeliste, drummer for New Orleans-based funk band The Meters. Modeliste needed a left-handed jazz guitar for his brother. Fat Dog took a regular jazz guitar and turned it over so the sound hole sits against the stomach, making the back of the guitar the front. Other wacky instruments he’s made include baritone lap steel slide guitars, baritone solid body resonator guitars, electric sitars and mandocellos.

It all happens in his Sonoma workshop.

Fat Dog’s interest in music started early. He grew up in Philadelphia with unionist parents who played music by activists such as Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. His mother told him that music was his weapon, and that led him to move to Berkeley in the mid-’60s, at the height of the civil rights movement. He studied medicine at UC Berkeley to not only avoid the Vietnam War, but because he thought he’d like to become a doctor after visiting impoverished parts of Mexico.

Fat Dog didn’t finish his degree, and instead became involved in Berkeley’s music scene, working part time buying, fixing and selling guitars.

“The cultural revolution was in such full bloom, and music was the weapon,” Fat Dog said. “Being involved in the music scene was like being a gunsmith at the height of the Revolutionary War.”

“The cultural revolution was in such full bloom, and music was the weapon,” Fat Dog said. “Being involved in the music scene was like being a gunsmith at the height of the Revolutionary War.”

He played guitar with several bands in high school but as an adult became more interested in guitar assembly and jamming with musicians. He opened Subway Guitars in 1968, but by the mid-’70s he needed a place to escape. He bought his property in Sonoma and splits his time between there and the Berkeley store.

The Sonoma studio feels like a roadhouse, a shrine of sorts to blues musician Chester Burnett (Howlin’ Wolf) — his name is etched on the room’s front door — and the sound Burnett brought to music of the 1950s and ’60s. No instrument in the space is newer than 1963, and the wooden floor gives a foot-stomping echo not found in modern studios.

“After 1971, music became so processed and artificial,” Fat Dog said. “Before then, music was spontaneous. What I’m trying to do is take it a step further by using recording equipment from the ’40s and ’50s to capture music that’s raw and has some richness to it, like that of John Lee Hooker, Otis Rush, B.B. King.”

Musicians looking for that vintage sound enter the recording space with a toddler-at-Disneyland enthusiasm, finding instruments they’ve never seen in person. Playing them, musicians can channel Burnett’s booming tone and record using wire recorders, tape recorders and 78 record-cutting machines. Nothing digital.

On the commercial side, Subway Guitars has been open for 48 years, rare for an independent music store. Stickers touting “Peace Through Equality” are attached to a wall.

“It’s not like a sterile Ikea-type of place,” Fat Dog said. “It’s more like the way guitar stores were in the ’60s and ’70s.”

“It’s not like a sterile Ikea-type of place,” Fat Dog said. “It’s more like the way guitar stores were in the ’60s and ’70s.”

He uses parts from Fender, Alembic, Modulus and others to create functional guitars for cost-conscious players.

In the 1970s, musicians from bands such as Jefferson Airplane, Creedence Clearwater Revival and Santana frequented the store. Members of Green Day hung out there. Michael Franti and Charlie Hunter worked in the shop. Paul McCartney plays one of Fat Dog’s guitars on tour.

“He has one of the best shops to find older instruments,” said the blues musician known as The Maestro. “He provides musicians with incredible instruments and makes them available at a real affordable level. He isn’t ever trying to rip the public off. He sets everyone up, creating a wonderful social situation around music.”

“Fat Dog has always stood for what he calls ‘the proletariat’ in terms of what he offers,” added Ethan Lee, who teaches music and works at Subway. “He doesn’t really care about shiny new guitars. He prefers to get something functional and make it available at a reasonable price for people. There’s massive gentrification going on in the Bay Area, but he’s continued to keep his lo-fi approach and offer entry-level and mid-range guitars to people.”

Sonoma is home to many guitar makers, yet none so storied — and private — as Fat Dog. For all of his shunning of the spotlight, his devotion to old-school musicianship and instruments looms large.